By Simone Bandini

“Harmony and disharmony combine, what agrees and what disagrees unite, and if Conflict is not the only father to all things, since it is inseparable from Union, Eros and Thanatos are at the same time in complementarity and in permanent antagonism”.

Heraclitus of Ephesus (550 – 480 BC)

“War is nothing but the continuation of politics by other means. War is therefore not only a political act, but a true instrument of politics, a continuation of the political process, its continuation by other means”.

Carl von Clausewitz, Vom Kriege (post. 1832-34)

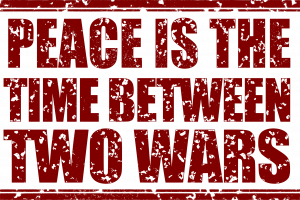

We start from the romantic albeit pragmatic thought of Prussian general Von Clausewitz to understand that, in the fundamental values of Western culture – from pre-Socratic thought to German Realpolitik – peace has never been never a value in and for itself – or at least it was never thought that it could be regardless of the matter of justice.

This absolutely post-modern invention of ‘peace for peace’s sake’ stems from the noble Enlightenment theorization of Abbot Charles-Irénée Castel de Saint-Pierre which had an important effect on thinkers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire and Immanuel Kant. Peace was born timidly as a ‘sentiment’, detached from any analytical and frank evaluation of reality, in a sort of moral and cultural makeover that considered humanity capable of erasing the, so to speak, ‘dark’ part of its nature. In particular, it was thought that the greatness of a sovereign and, therefore also, sometimes, the justification for war, did not derive from the vainglory deriving from military expansionism, but from the increase of wealth of his people, from which the prestige, the magnificence and the very wealth of the sovereign him or herself. A sort of absolute theodicy of money was making its way, which in the centuries to come would be refined into materialist ideologies such as communism that banished the spirit, and its complexity, from the story of humanity.

Pacifism amongst our contemporaries, more and more, has lost all rational foundation, totally detaching itself from political reality, boasting alleged ethical foundations in the conviction that war is morally wrong and that this “action of attacking and bullying and even killing” can never be justified, is extraneous to the true essence of humanity and, in fact, is against nature, materially and morally.

In the twentieth century, after the great world wars, pacifism then transposed itself into the transient utopianism of the beat generation achieving recently, after two thousand years, a fusion with a modernised and completely worldly Christianity, which has lost its relationship with the sacred and shows itself indifferent to the fetishes of ‘fluid’ thought and ‘gender’, clearly navigating through the chaotic miasma of ‘cancel culture’.

Here we can only reaffirm the conviction that peace is a desirable (but not absolute) good, and that it must proceed from the concept of justice. And that if you really want to win peace – you have to do it with a complex philosophy of the spirit, rather than with a mere act of erasing its counterpart. Which is moreover, useless.

Recommended listening: “Try better next time”, Placebo