By Federico Donti

The editorial staff of our newspaper turned to the Catha association, at the multimedia museum “Rasna”, in via Roma n°15 in Perugia, to verify if there are connections between the city of Foligno and the Etruscan civilization, believing to do a meritorious work for the city that appears on the cover. Reached the prestigious Rasna museum, we found the president of the Catha association Luciano Vagni and the representative of the UILT-Italian Union of Free Theatre, Lauro Antoniucci, waiting for us.

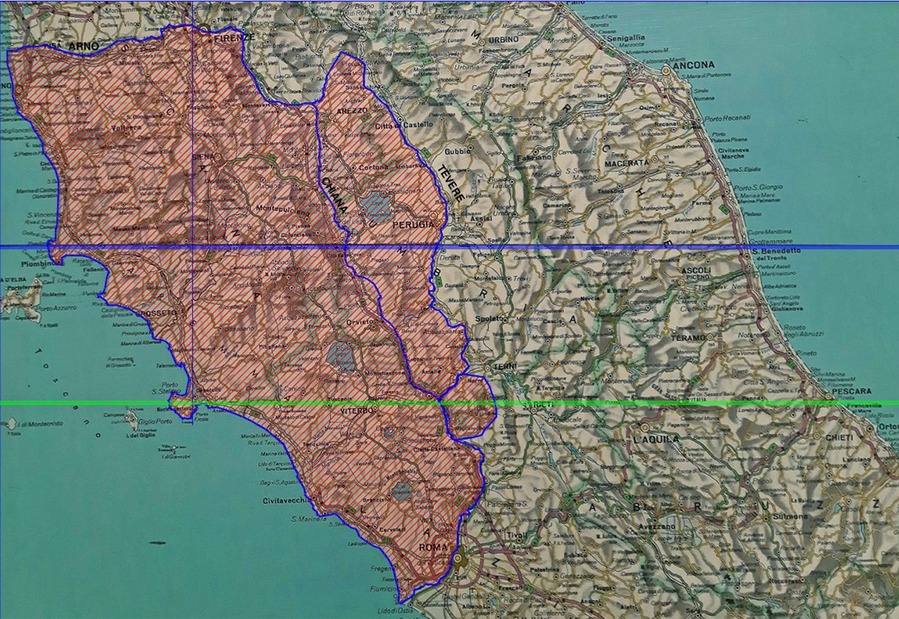

I asked Lauro Antoniucci if it is possible to find evidence of the Etruscan civilization in Foligno, or in the surrounding area. So I immediately got a scramble from Antoniucci who expressed himself as follows: “A significant testimony exists, and it is as big as a mountain, and you dealt with it in issue 177 of your magazine, autumn/winter 2024. This is the Sasso di Pale, the trigonometric point created by the Etruscans to define the decumanus maximus of Etruria, the sacred line located at the widest point of Tuscia, which exactly joins Populonia, the Etruscan Fuflona, the city of Sarteano (Satres), and the Sasso di Pale, passing through Deruta and the historic Collemancio. (photo promontory of Populonia and Pale stone). You must remember that the Pale stone contains the hermitage that was awarded by UNESCO on 12 October 2024 with the “The factory in the landscape 2024” award. This important trigonometric point is the greatest testimony of the relationship with the Etruscan civilization of this area.

Q.: “So you claim that the city of Foligno, due to its position, had particularly intense relations with the Etruscan civilization?”

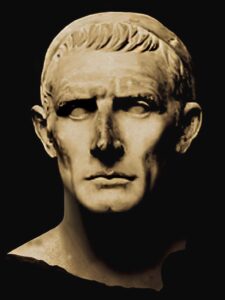

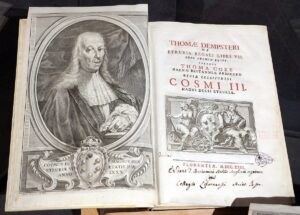

A.: It is not me who says it, but the most famous Roman historian of the period of the birth of the empire, Livy, who writes: “ab alpibus ad fretum siculum totam italiam etruscam esse” (i.e. “all of Italy was Etruscan from the Alps to the Strait of Messina”). This makes it clear that the Etruscan civilization is far prior to the Roman one, as evidenced by sixteenth/seventeenth-century historians, such as Thomas Dempster in his famous “De Etruria Regali” which documents over ten centuries of Etruscan history. However, this is ignored by most of the world of culture which is led by the books circulated by many archaeologists of the last century, to believe that Etruscan history begins from the ninth century BC, that is, just a century before the foundation of Rome.”

A.: It is not me who says it, but the most famous Roman historian of the period of the birth of the empire, Livy, who writes: “ab alpibus ad fretum siculum totam italiam etruscam esse” (i.e. “all of Italy was Etruscan from the Alps to the Strait of Messina”). This makes it clear that the Etruscan civilization is far prior to the Roman one, as evidenced by sixteenth/seventeenth-century historians, such as Thomas Dempster in his famous “De Etruria Regali” which documents over ten centuries of Etruscan history. However, this is ignored by most of the world of culture which is led by the books circulated by many archaeologists of the last century, to believe that Etruscan history begins from the ninth century BC, that is, just a century before the foundation of Rome.”

Q.: “And why would archaeologists have made the mistake of ignoring historians?”

A.: “According to the reconstruction carried out by the experts of our Catha association, this is due to the fact that archaeologists believe what they see, like St. Thomas, and have based themselves above all, as the famous archaeologist Luisa Banti has clearly stated in “Etruscan Studies – year 1936″, on tombs, ignoring that they may have begun to preserve the ashes and bones of the deceased, which were previously evidently dispersed, around the ninth century BC, in the period of transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age. In this period the metamorphosis of the Italic peoples took place, including the Etruscans, who began to detach themselves from the community and participatory relationship to the life of nature, to begin a possessive and competitive relationship between peoples and within them: the economic oligarchies were born and the monarchy of Rome is a testimony to this as represented by the Roman cycle of the ‘Francoise’ tomb.”

Q.: You show us a mountain, that of Pale, as a testimony, but isn’t there by chance some written document that attests to a relationship, in this Umbrian area, with the Etruscans?”

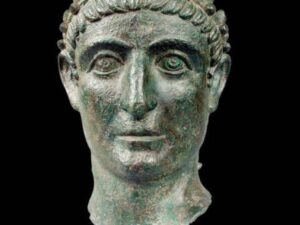

A.: You know very well that writing was practiced by the Etruscans at the time of the kings of Rome; they probably learned it from the Phoenicians before the Greeks, but there are no documents to confirm this. But at the time of the Roman occupation of these places, an important document dates back, the famous “rescript” document of Spello, which demonstrates the participation of the citizens of these places in the famous meetings near Orvieto, of the Fanum Voltumniae (photo).

A.: You know very well that writing was practiced by the Etruscans at the time of the kings of Rome; they probably learned it from the Phoenicians before the Greeks, but there are no documents to confirm this. But at the time of the Roman occupation of these places, an important document dates back, the famous “rescript” document of Spello, which demonstrates the participation of the citizens of these places in the famous meetings near Orvieto, of the Fanum Voltumniae (photo).

The rescript of Spello reports a provision of the emperor Constantine who allowed the Umbrians to celebrate at their seats the annual religious ceremonies and the games connected to them, which were traditionally celebrated by the Etruscans “apud Volsinii”, which was the place where the political/religious rituals of the Etruscan federation took place. Therefore Spello, a city also crossed by the decumanus maximus of Etruria, has the concession from Constantine to carry out games and ceremonies in his city.”

Q.: Mr. Vagni, since you are smiling, would you kindly explain to us what the decumanus maximus of Etruria is, and why in this area, between Sarteano and Orvieto, and probably even beyond, such important things have happened for centuries?”

A.: “Our geography is made up of meridians and parallels, horizontal lines parallel to the equator and vertical lines, passing through the poles. The Etruscans had identified these lines so much that they defined them as sacred, that is, lines of the sky that allow us to orient ourselves on earth.

The decumanus are therefore lines in an East/West direction and those of maximum or minimum length within a territory were defined as sacred. In Etruria the line of greatest width was the decumanus passing through Populonia, as the promontory of Populonia allowed for a point of greater width. The problem of preserving the sacredness of the decumanus maximus arose when, in the fifteenth century BC, the Pelasgians proposed to the Etruscans to expand the territory of Etruria eastwards, incorporating areas historically inhabited by the Umbrians. This process of expansion certainly occurred in a peaceful way, following a cultural expansion that was underway, as Livy described to us, and which testifies to an Etruscan culture spread throughout the Italian soil. The problem of the Etruscans was not to desecrate their territory, thus keeping the sacred lines unchanged: they could not carry out an expansion that would change the maximum decumanus of the ancient part (southern part of Etruria passing through Vulci, Tuscania… etc.) and of the postica part (northern part) passing through Populonia.

To keep these sacred lines unchanged, the Etruscans probably had to modify Tuscia and part of it.

In the decumanus maximus of the ancient part, so that it would not be overcome with the enlargement of the northern part, they extended their territory also to the area that includes Narni and Otricoli, reaching with the decumanus as far as the locality of Configni, whose name indicates the border between the Etruscan confederation and other peoples; It is interesting to note that this decumanus, crossing Otricoli, hypothesizes its Etruscan foundation, and, therefore, invites us to search for Etruscan emergencies below the Roman layer.

The decumanus maximus of the postica part passing through Populonia with the extension to the east, up to the Tiber, becoming of the same length as that passing through Perugia and S. Vincenzo on the Tyrrhenian Sea, risked being exceeded (the issue of Valley Life n.177 on page 30 shows the plan with the two decumanus); to avoid this danger the Etruscans were induced to divert the Tiber from Lidarno to Ponte Valleceppi; there is no historical memory of this deviation, but the fact that the place is still called Lidarno, that is, “Lido dell’Arno” suggests that the Tiber flowed in that place which, at the time, was called Arno”.

The decumanus maximus of the postica part passing through Populonia with the extension to the east, up to the Tiber, becoming of the same length as that passing through Perugia and S. Vincenzo on the Tyrrhenian Sea, risked being exceeded (the issue of Valley Life n.177 on page 30 shows the plan with the two decumanus); to avoid this danger the Etruscans were induced to divert the Tiber from Lidarno to Ponte Valleceppi; there is no historical memory of this deviation, but the fact that the place is still called Lidarno, that is, “Lido dell’Arno” suggests that the Tiber flowed in that place which, at the time, was called Arno”.

Q.: “Basically, in your opinion can Foligno be considered Etruscan or not?”

A.: “The area of Foligno was not part of the Etruscan confederation, but of the Fulginati people who were part of the Umbrian federation of which no significant traces have yet been received; the Etruscan presence was certainly cultural, as Livy and Constantine made us understand. The nearby Bevagna (etr. Mefana), Cannara (Urvinium Hortense) and Collemancio, have important signs of the Roman era that show significant Etruscan cultural influences.

But most of all the nearby stone of Pale, built by sculpting a sacred mountain because it is located on the sacred axis of Etruria – is the maximum sign of the relationship of cultural sharing; the rescript of Spello testifies to the intimate relationship with the Etruscan civilization, participating in the same community festivals, the same games and musical and political events; a relationship that, as the rescript itself attests, ends with the conquest of Rome.”